SSEF jewellery collection: a brooch by René Boivin (1944)

A Croix de Lorraine Clip-brooch, by René Boivin, 1944

In 2022 the SSEF began its project of establishing a jewellery collection illustrating the history of jewellery to accompany the Advanced History of Jewellery Course held at SSEF (next taking place July 15-19 2024 in Basel). I was thrilled by this visionary approach – and grateful for this unique opportunity to source such a variety of jewellery through the ages.

Soon I found the Croix de Lorraine clip-brooch by René Boivin. To have a piece by René Boivin in the Collection was of course a dream, not to mention starting it with a Boivin piece… I fired off a few arguments why the SSEF should really buy this brooch. It just ticked all the boxes:

The House of René Boivin

The House of René Boivin (or Jeanne Boivin, really…) is an icon in the history of 20th century jewellery design. In early 2006 I was cataloguing the Christie’s Geneva sale. My learning curve was vertical if not looping backwards. I still remember when one day nine extraordinary jewels landed on my desk: amongst them a starfish encrusted with amethysts and cabochon rubies, an orchid with yellow and white diamonds and a pair of sapphire and diamond bindweed flowers. Never had I seen such sculptural, naturalistic jewels; they were almost alive and not afraid of their weight. The colour combinations of some of the pieces in that collection were extraordinary. Talking to Françoise Cailles on the phone, I remember her as a very kind lady who was much bemused by my French (and even more so by my last name). Of course the novelty at the time was overwhelming but these jewels “stuck” with me and although at the time I did not fully grasp the genius of Boivin, they gave me a good taste of it.

In 1893, two years after setting up his workshop, the jeweller René Boivin married Jeanne Poiret, sister of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. She started helping him with the administration of his workshop. Through Jeanne’s brother they moved in circles with progressive tastes in art and fashion and soon René started to make jewels for these fashionable intellectuals and artists who wore his brother-in-law’s clothes. The seed of Boivin jewellery being different was planted.

A Woman Taking the Lead

However, in 1917 René and in 1918 their son Pierre died in battle during World War I, mort pour la France. Uncharacteristic for a woman at the time, Jeanne decided to take over the running of the company and to keep fulfilling the orders they had already committed to. She had very clear ideas about how a jewel was to look and feel like, and her vision was unfettered by any formal education as designer or jeweller. Her jewels were a collaboration of her ideas and the workshops’ skills. In 1919 she hired the 19-year-old Suzanne Belperron as designer who would, in 1932, leave to set up her own company. Soon the two women gave up “standard designs” for good: a complete departure from prevalent contemporary design (geometric, flat, mostly monochrome and using platinum) her jewellery, often mounted in gold, was flamboyant and different with its curves, colours, unusual materials and techniques. Her jewels had volume and were highly tactile, they were jewels designed by women for women. Jeanne Boivin not only continued the legacy of René but she distilled it, reinforced it, went even further and came out with a flourish of new designs, ideas and techniques to almost single-handedly change the history of Western jewellery design. René, however, was always to remain part of the company’s name. The jewels were rarely ever signed – too different were they from the rest of the pack so she did not think signing them was necessary: you could see from afar that the gold-studded wooden ring or ivory cuff with gold polka dots were her creations. This makes identifying them sometimes a little tricky. However, awareness has increased since the sale of the jewels of the Duchess of Windsor

in 1987 where many (of course unsigned) Boivin pieces were only later identified. Luckily the entire René Boivin archives have miraculously survived, and we are all on our toes awaiting the definite book by Juliet de La Rochefoucauld on René Boivin to come out in 2025. A reliable identification service backed up by the extensive archives is offered by their curator Thomas Torroni-Levene.

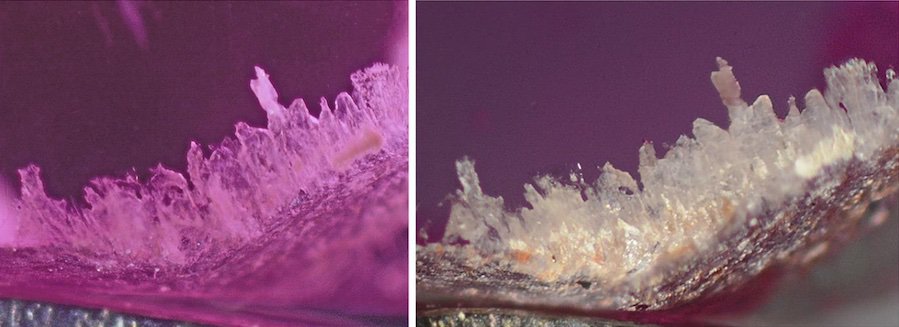

The Jewel’s Tattoos

As every step of the making of the jewels was closely watched over by Jeanne, Boivin’s jewels have a special sensuality to it and the quality is impeccable. Although she had a main atelier Boivin also worked together with a few others. Our Croix de Lorraine clip-brooch is typically unsigned but carries a beautiful maker’s mark of CHP flanking a mistletoe for Charles Profilet, one of Boivin’s favourite workshops. It also came with an older certificate of authenticity – just to put everyone at ease. We find the eagle’s head for 18K gold in all the right places – on the pins and on the cross itself as stipulated by the French assay office. The pins are typically made of pink gold as its higher copper content makes them springier (but also more difficult to work with). The back is engraved “AOUT 1944” (see below).

The Cross of Lorraine and its History

Those well versed in French history will have spotted straight away that the mere shape of the double cross, the Croix de Lorraine, was used by the French Resistance against the Nazi occupation during World War II. The double cross has its origin in Byzantium and came to the Duchy of Lorraine in eastern France probably via Hungary in the late 12th Century, where it was used as a symbol of royal power. In 1477 René II, Duke of Lorraine carried the double cross on his flag into the Battle of Nancy where he then defeated the occupying Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. When Lorraine was annexed by neighbouring Germany between 1871 and 1918, the French used the double cross to rally for a recovery of their lost territory. When France was occupied by Nazi Germany between 1940 and 1944 the Croix de Lorraine was again an obvious choice, thanks to its long history of resistance against invaders, for the Free French Forces led by Charles de Gaulle to symbolise the French Resistance. The engraving “AOUT 1944” gives us a further clue to its historical context: Paris was liberated in a battle between 19 and 25 August 1944 when the Nazi occupants finally surrendered and de Gaulle declared that France freed itself, relegating the Allied Forces to a mere mention in the middle of his victory speech… Our clip is a jewel celebrating the Resistance against and victory over Nazi occupation – it is an object deeply meaningful to its original wearer and contemporaries and heavily charged with emotions: in all probability with relief and joy – but perhaps also with grief for lost ones.

The Rubies

The carved rubies are typically of very low gem quality. They are a vestige of pre-war Art Deco jewellery in the so-called “Tutti Frutti” style (a term invented in the 1970s) made famous by Cartier: Jacques Cartier had set out to India in 1911 to encounter the colourful world of India and her maharajas bejewelled from head to toe in magnificent pearls, multicoloured gemstones and large quantities of diamonds. It was a landmark journey and apart from making important client connections and purchases he also brought bags of little ruby, sapphire and emerald pebbles carved into fruit and leaves. Inspired from his travels Cartier would set them in colourful “exotic” compositions such as bracelets, necklaces and “fruit bowl” brooches but, unlike their Indian counterparts, mounted in platinum and not gold, thereby fusing Indian influences with Western taste. Although Cartier were not the only ones, Cartier was particularly famous for it and their rare Tutti Frutti jewellery still reaches record prices. During World War II precious stones and metals were of course rationed: platinum was used in the production of arms, and it is almost completely absent from jewellery made during or immediately after the war. Gold, on the other hand, has been used since antiquity to finance war efforts. War-time jewellery was therefore made from jewellery brought in by the client and which was to be recycled. Perhaps those rubies were previously set in a platinum Art Deco “Tutti Frutti” jewel?…

The Beginning of the SSEF Jewellery Collection

Finally, the historic context makes the clip a great study or museum piece. However, the meaning of the Croix de Lorraine and its relevance is mostly lost on us today, so it is not a very wearable piece of jewellery. And that’s the last box our clip is ticking off: not very wearable is polite speak for “the price is right”. It just took about 10 minutes and a couple of exchanges to get the final OK for the inaugural piece of the SSEF Jewellery Collection. No red tape. Of course, I was on a high for a few weeks. Who would have thought the SSEF could be such an endorphin booster?

I wish to thank Juliet de La Rochefoucauld for pointing out a wrong date and for her opinion on the stylistic development. Any errors that remain are of course my own. Thomas Torroni-Levine graciously helped at the last minute.