Unravelling the secrets of antique jewellery

By Dr. M.S. Krzemnicki, first published in Facette 29 (May 2024)

In the following, we would like to present a few interesting cases which we came across in past few months at SSEF:

Early replacement:

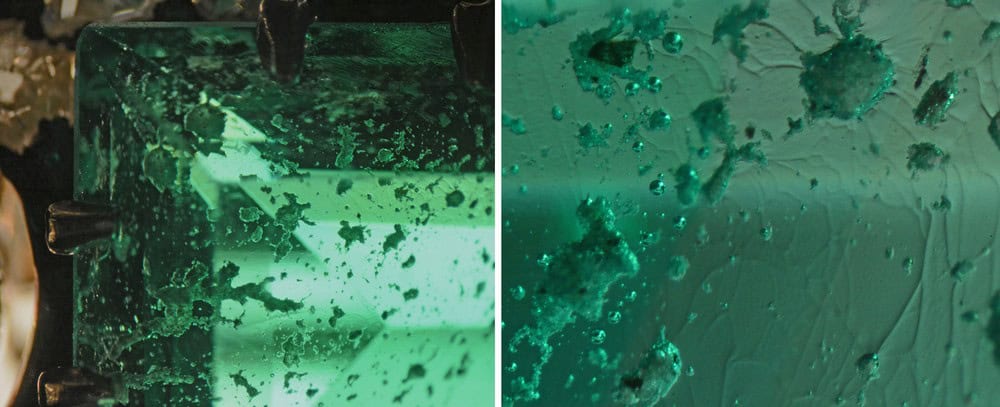

Recently, the SSEF received a brooch of late 19th century design set with old-cut diamonds and a rectangular emerald green stone in the centre (Figure 1). Upon closer inspection, however, some doubts arose as distinct wear marks, smoothed-out facet edges, numerous scratches were seen under the microscope, pointing towards an emerald imitation made of glass (paste). Chemical analyses quickly confirmed the glassy nature of this green stone, consisting mainly of lead, potassium, and silicon and coloured by traces of chromium. Such glass is historically known as flint glass and characterized by a higher refractive index, lustre (brilliance) and density compared to normal (soda) glass. Interestingly, this green glass not only contained numerous tiny air bubbles, but also rather prominent inclusions of spiky irregular shape – by the naked eye quite convincingly imitating the jagged fluid inclusions well-known from Colombian emeralds (Figure 2).

The remaining question is: at what stage was the green glass stone set into this 19th century brooch? Based on the fine quality of the setting and diamonds, we assume that the brooch originally contained a real gemstone, most probably a Colombian emerald, which may have been heavily damaged and needed to be replaced by a green look-a-like. Given the included (old) nature of this lead glass and its wear marks, we assume that this replacement is not recent but already happened during the late 19th or early 20th century.

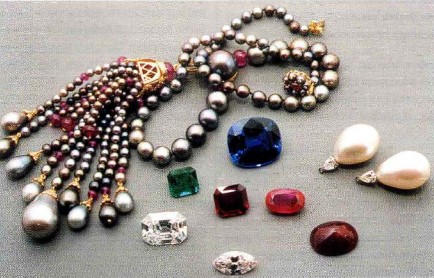

Re-use of gemstones in antique jewellery

It is quite common that old and out-of-fashion jewellery is drastically redesigned so as to be again attractive for a new and younger generation. This is very much in difference to visual arts such as paintings and sculptures, for which such a change and re-use would be considered quite a sacrilege.

When old jewellery is re-designed and adapted to a new style and use, it often also means that the original gemstones are re-shaped and re-cut to fit in the new design and setting.

Historically, we know that such re-cutting was a very common practice as access and availability of gemstones of high quality was far more limited than today. But evidently, this practice continues up to the present day. Although in certain cases this leads to a loss of original appeal and historic reminiscence, such re-cutting may also offer interesting insights, specifically when it manifests itself in the gems re-used in a new setting.

A close look at one of the faceted Sri Lankan sapphires (which fell off the necklace) shows that the V-shaped half-drills at the tip of the stone are only shallow and thus create a very fragile suspension situation (Figure 5). In contrast to this, such drill holes in ancient gems were commonly very deep (often even penetrating throughout the gem) to allow for a stable fixation of the gem on the jewel and dress decoration. We thus assume that the present shape and faceting is actually the result of a re-cutting process. Presumably, the initial sapphire was a rather baroque-shaped and polished bead with deep V-shaped drill holes and was mounted on an even more historic jewellery piece. It thus was recut and faceted into its present shape now exhibiting very shallow drill holes. The cutting style (large culet facet), the strong wear marks at the facet edges, and the chatter marks on the pavilion of this sapphire and all other faceted gems on this necklace indicate that this postulated re-cutting may have been carried out in historic times, most probably already in the 17th – 18th century.

The final case in this survey on antique jewellery is about a sapphire which was originally mounted as a centre stone in an antique diamond brooch reportedly from circa 1880.

Gemmological testing clearly revealed it to be a sapphire of Sri Lankan origin. The stone had been recently repolished to remove small blemishes and knock marks. However and interestingly, this sapphire exhibits on the backside a long linear bulge, visible even from the front side (Figure 6). Based on the antique setting, the cutting proportions and style (slightly convex table facet), we assume that this polished linear bulge on the pavilion side of this sapphire is a remaining feature of an originally present large drill hole in an even more historic and larger sapphire. As the stone is nearly free of any inclusions, we consider it rather unlikely that this polished bulge was made to remove a large straight inclusion feature in this sapphire.

To conclude, as mentioned at the beginning, the testing of antique jewellery and their gems may provide insights that stretch far beyond routine gemmological testing. The re-cutting of gems over centuries is well-known and relies mainly on the fact that gems are not perishable consumables. Gems are actually here to stay and serve to embellish and fascinate not only people from the past and present, but also those coming in the future, be it in their original historic state or as a newly redesigned and re-cut gem and jewel.

For those who would like to learn more about these and further fascinating findings related to antique gems and jewellery, we suggest you enrol in our Advanced Course in Jewellery History, that will next take place July 15-19 2024 and in January 2025 (www.ssef.ch/courses).